A radical future?

The Innovation Matrix

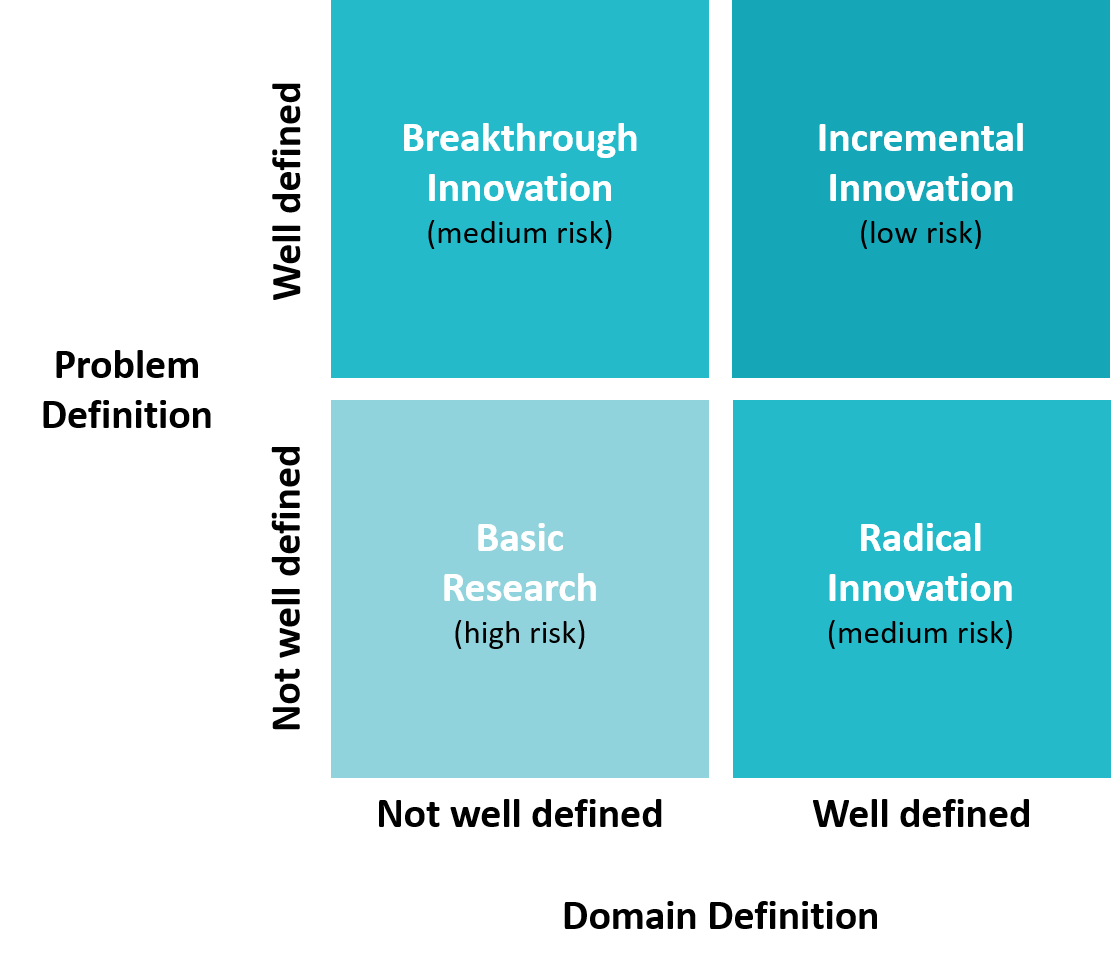

There are lots of different ways to think about new products, services or businesses. One that I find helpful is that of the Innovation Matrix. A quick word of warning, the language used to describe these things is often not used in the same way. Different people use the same or similar terms to mean slightly different things. I will try to be consistent but some models I link to may need a little bit of translation to ensure all the terms are the same.

A simple 2x2 matrix (business schools love 2x2 matrices if you haven’t noticed already) that has Problem Definition, how well the customer need is understood, plotted against Domain Definition, how well the implementation challenges are understood.

So for example, if the user need (Problem) is understood, our customers want a bigger one, and we know how to do that (Domain) then the opportunity is an Incremental Innovation. But if we know how to make something, but don’t yet know how customers will use it or how it might change society as a whole (flying cars) then it’s a Radical Innovation.

The categories are not precise and some examples could be either. But it’s a helpful guide that can influence how you manage your own innovation activities.

Basic Research:

Where everything ultimately starts, but probably not by you.

Exploration, the discovery of something completely new, usually performed by universities, academic institutions and research centres and is often funded by governments. Predictably this is the highest risk innovation strategy and is unlikely to provide actionable results that will lead to commercial success for the funding company. However many firms support and invest in basic research despite these market realities because they believe it helps them attract the best talent and gives them many ‘soft’ non-financial benefits. Examples might include, Cancer research, Maths, Engineering and Physics PhDs.

Xerox had a very famous research facility in California that pioneer many of the technologies we take for granted today. But Xerox failed to commercialise most of them.

Breakthrough Innovation:

Basic research can move to either a Breakthrough or Radical. Because the problem is known, this could also be described as a Market Pull Innovation.

Bold, dramatic bets on the future. Solving a known problem, but one currently very hard to solve because the technology is not yet developed to do the job. The government / military are keen on breakthrough innovations and often issue grand challenges to engineers around the world to try and solve (DARPA’s self-driving car challenge helped kick-start the autonomous car industry). Putting a man on the moon, new Cancer drugs or Google’s internet transmitting balloons might be good examples.

January 2021 Update:

With Google’s recent announcement that they will be shutting down their “Project Loon” after 9 years of trying to get it to work and stand on it’s own feet, it reinforces this idea that Breakthrough innovations are a battle of technologies rather than customer demand. We all want internet wherever we are in the world, but there are now better ways of providing that than Loon… no one imagined 9 years ago that we could put tens of thousands of little satellites into orbit economically. But the rise of mega cluster satellite constellations has hit everyone by surprise.

Radical Innovation:

The technology is known, but not how it will be used, so could also be described as a Technology Push Innovation.

Typically described as a step change in capability, beyond usual incremental development. Radical is technology (or supply) push, whereby a new technology has not yet found its clear need. Examples could be the very early days of televisions, computers or cars.

Flying cars are a good current example where lots of companies are trying different ways of making it work, but no one design has yet come to define a flying car. Like televisions, it’s a chicken or the egg scenario, no one has a TV because there isn’t yet the infrastructure to make TV shows. No one knows what they would watch it for (since there is nothing yet to watch). The technology has been created before the user knows why they need it.

Incremental Innovation:

The vast majority of all activity and ultimately where everything else ends up. Once people start to adopt radical or breakthrough innovations, they can quickly become incremental.

Since both the domain and the problem are known, this is the lowest risk strategy to follow and should be the majority of a company’s development effort (perhaps as much as 70%). The seemingly gradual advancement of an existing product or service from it’s early bold arrival. Examples are plentiful, the yearly release of new phones with improvements in performance each time.

The improvements do not need to be small, incremental does not mean little or boring. But it’s a lower risk activity because we’re very confident the customer wants whatever it is we’re making.

Note that the language used in this diagram is slightly different to the above matrix, but it should still be easy to understand and I believe the intention is still clear.

This diagram, or something similar, is an often cited guide to where organisations should focus and balance the risk in their portfolio of innovation activities. The majority, should be low risk, incremental work improving the things you already know. Then 20% is what they call Adjacent but is probably best mapped onto both Breakthrough or Radical Innovations. Finally 10% might be considered Basic. Developing an underlying foundation for future offerings, whatever they might be.

Dominant Designs

When Radical becomes Incremental

“A dominant design is a standard that defines what a product is and what its core features are. It’s a platform from which come a wide range of variants that are distinguishable from one another without being fundamentally different. The core features of the product effectively set parameters of performance that all variants built off the same platform share.”

- Constantinos C. Markides and Paul A. Geroski (Harvard Business Review 2008)

The world before and after Ford.

In his early days Henry Ford was an engineer for Edison and became his Chief Engineer. Through this he was able to experiment with gasoline engines and started building racing cars. Over the next four years he would found three car manufacturers… The Detroit Automobile Company (which lasted only two years), the Henry Ford Company (which became Cadillac when he left it and is still a car brand today) and then finally in 1903 the Ford Motor Company.

Is it surprising that the father of the modern car was involved in so many different startup car companies? Not really, it’s a classic Radical Innovation scenario. Lots of people all desperately trying to be “the one” who defines a new opportunity and dominates the market.

At the time, there were hundreds, perhaps even thousands of car companies in the US. All desperately trying to out innovate each other for the small number of people who could afford one. The road system was not designed for cars, they were a play thing for the rich and famous, not an established consumer market and no one could agree on which technology might be the best…around 40% were steam powered, another 40% were electric and only 20% gasoline.

So it is against this backdrop that Ford’s Model T was launched in 1908. The world’s first, affordable car and the rest is history.

Most of the car industry could not compete and over the next few years died away as Ford’s prices dropped further every year. Fascinatingly taking with them the hopes and dreams of steam and electric car enthusiasts as well and giving us 100+ years of gasoline dominance.

The Ford Model T was a dominant design and from then everything became Incremental.

Every car that followed looked somewhat similar to and worked in a similar way to a Model T. So popular was it that after a few years almost every American had learnt to drive in a Model T and so every other car needed to resemble one as well.

The moment the Model T took off was the moment the industry moved from being Radical to Incremental. No longer a niche play thing but a serious mass market product and the need changed from being market defining to market improving.

FAQs

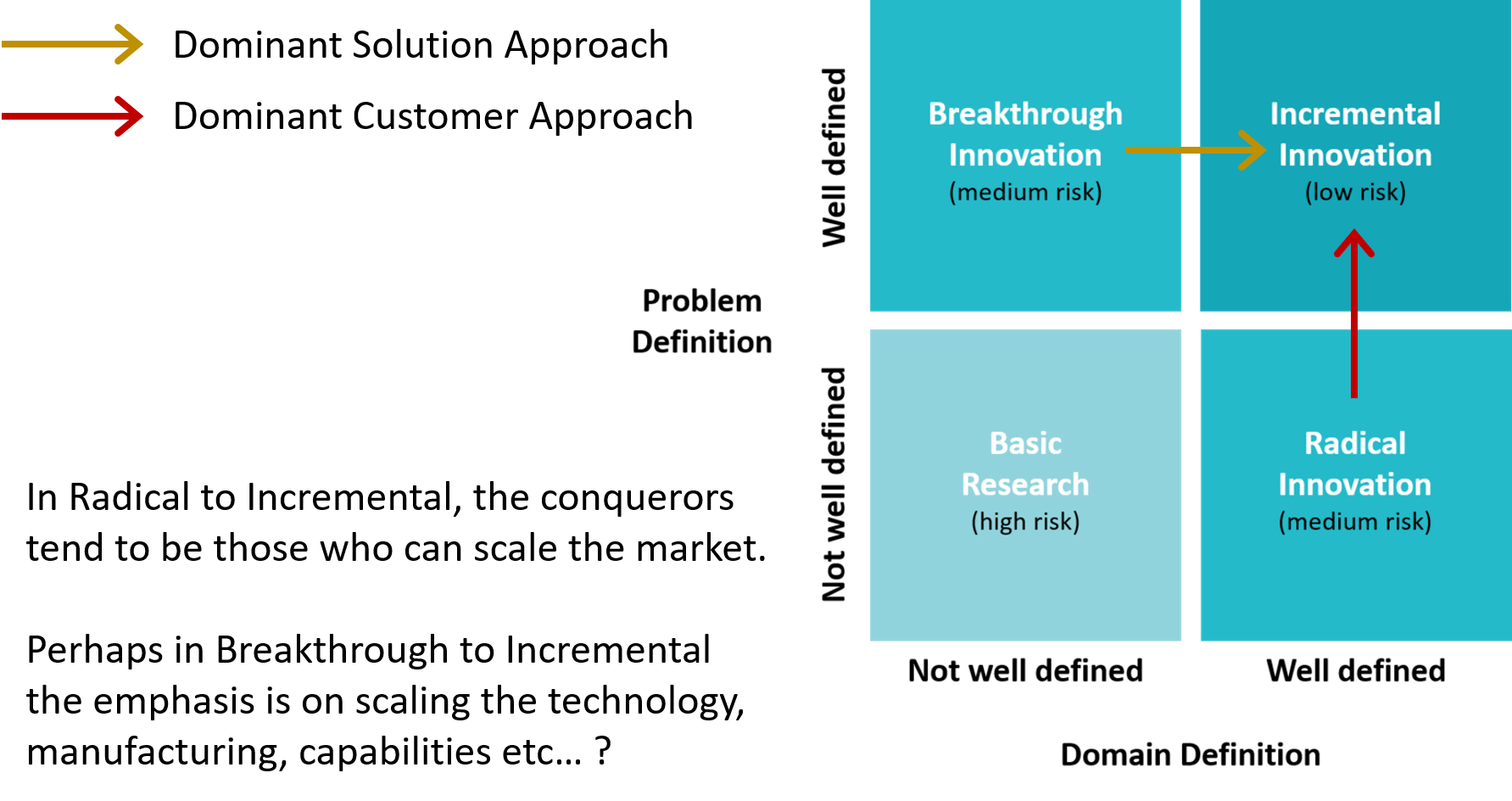

Is there a nuance to [the role of Pioneers & Conquerors] for “Breakthrough” innovations? Since there is already a clearly defined demand for the product, would the conqueror’s role be much less prevalent (or at least of lower risk)?

Very interesting question, I’ve not seen this discussed in the theory but my sense would be that it’s similar. The appearance of a dominant design signifies the transition from a Radical to Incremental innovation challenge. But there must be a similar transition from Breakthrough to Incremental. The difference however is that rather than a discovering the dominant customer desire (market) in this transition it’s the dominant solution approach which is discovered.

So the skill set of the conqueror is different in this scaling challenge. Rather than having access and the ability to take a product to a mass market once the correct market segment has been identified, the requirement of the conqueror here is the ability to deliver on the required technology. For a breakthrough project like Google’s Loon, perhaps a large established aerospace company such as Lockheed or Boeing would be far better placed to take this idea into the mass-market, and thus ‘conquer the market’.

Once a dominant design has been established for a type of product is it common that brand new technology renders that dominant design insignificant and a new one is established?

I believe it’s quite common, products tend to go through different transitions, so whilst they are still performing a similar function the customer expectation of what it is and how it works may change. The phone is an easy to understand example of this:

But one thing to consider is what do you class as being ‘the product’? A car for example still resembles the Model T, steering wheel, 4 wheels etc… but the engine, functionality and control has undergone significant change in the last 100 years.